Dogme 95 was an avant-garde movement of film created in 1995 by Danish directors Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg. The directors believed that cinema had fallen into overly aesthetic and thematically vapid cinematic decadence and proposed an alternative in an attempt to revisit a time in film history before contemporary trends had overtaken filmmaking. After discussing how they wished to pursue this new ideology, they created the Dogme 95 manifesto and its Vows of Chastity.

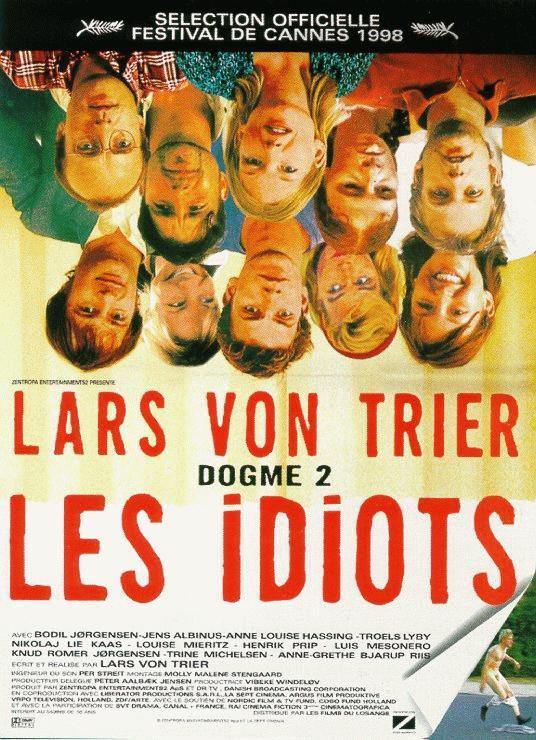

The Idiots (1998, von Trier) was among the earliest films made within the Dogme 95 movement, telling the story of a group of young men and women with anti-bourgeoisie ideals who pretend to have mental disabilities in an effort to both disturb and reject the society in which they live. The film makes full use of explicit and disturbing imagery, ranging from emotionally raw scenes such as when one of the group is taken away to an explicitly shot orgy scene.

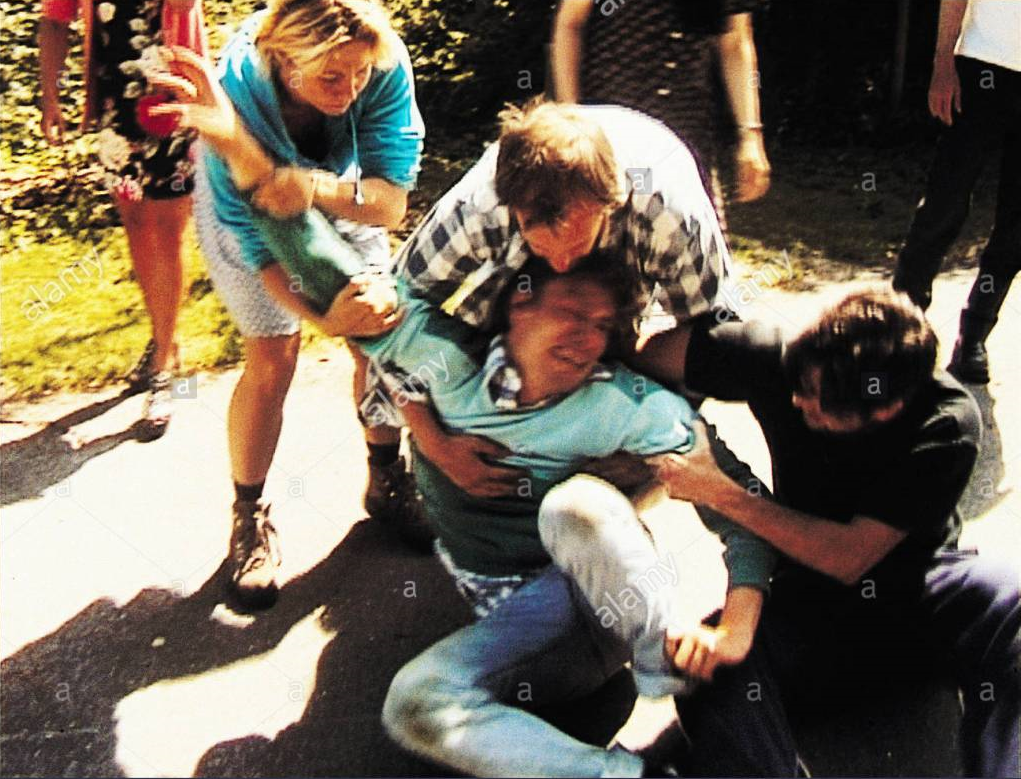

In many ways, The Idiots is representative of the Dogme 95 movement as a whole. As Walters describes “[…]precisely because of its many imperfections and discomforting subject matter, The Idiots may be the most fully developed and compelling expression of Dogme ideology. The meaningfully artless form and content of The Idiots are intertwined in particularly unique and revolutionary ways, enabling the film to critique contemporary film and contemporary culture.” (Walters, Tim. Reconsidering The Idiots: Dogme 95, Lars von Trier and the Cinema of Subversion?). The term “meaningfully artless” is particularly interesting. In many ways, the use of its low budget and almost amateurish style in some ways enhance certain aspects of the film. A scene that exemplifies this is the scene in which one of the group is forcibly taken away from the group, and the protagonists desperately attempt to prevent this, only to fail. Due to the lower grade of film, the handheld style (even seeing the camera operator’s shadow) and the distinct lack of music, it creates a pseudo-documentary style and equally draws the viewer in as much as it alienates them. It creates the illusion that this is painfully and uncomfortably real, something that the ‘decadent’ mainstream would potentially fail to achieve.

The characters “spassing” can be read as a representation of von Trier’s frustrations with mainstream contemporary cinema. The society that they are attempting to provoke fits within a very strict set of rules that care more for the aesthetic than the content itself, while the characters reject this notion and act out in these ways as a form of protest, as well as “to take the piss”, much like the foundation of Dogme 95 itself. The film culminates in the aforementioned orgy scene, in which the characters remove their self-imposed restrictions and have sex while “spassing”. This act of pure unreserved and unstructured expression can be read as a “[…]self-reflexive allusion to the technical prescriptions of the “vow of chastity” that each Dogme film must adhere to, forging a critical connection between the transformative power of unmastering oneself both as a director and with regard to the practices of everyday life.” (Walters, Tim. Reconsidering The Idiots: Dogme 95, Lars von Trier and the Cinema of Subversion?) While uncomfortable, the sheer power of this scene is tangible and is an example of the potential of something such as Dogme 95’s rejection of standard film language, but instead puts the events and human struggle above all, as well as the potential for films over all.

Dogme 95 ended in the early 2000’s, ironically due to von Trier and Vinterberg believing that is was becoming too mainstream. While the movement was short, to consider it a failure is perhaps not giving it the credit it deserves. It not only is a glimpse to the power of film, the potential of any those with an idea and a camera, but pushes the boundaries and structures that we allow ourselves to be contained within. This meaningfully artless movement ended how it began, challenging the norm and on its own terms.

Works Cited and Further Reading:

Walters, Tim. Reconsidering The Idiots: Dogme 95, Lars von Trier and the Cinema of Subversion?

The Idiots

Behind The Rules Of Dogme 95

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2012/nov/25/how-dogme-built-denmark