During its early life, Czech cinema was strong and stable, for the time period. Beginning comparatively later than their foreign counterparts in France and Britain, their cinematic form began in the 1920’s and movements such as the Devětsil, an avant-garde Czech group that, from 1923 onwards, focused on the idea of Poetism. They preferred to explore the proletarian struggle, finding art, beauty and intrigue in the everyday, with one of its most prominent members, Karol Teige, remarking that “The most beautiful paintings in existence today are the ones which were not painted by anyone.” (Karel, Srp (May 1999). Karel Teige in the Twenties: The Moment of Sweet Ejaculation). However, this unfortunately was not to last, for in the mid-20th century, the country was successfully occupied by the Nazi party during World War II and their culture was assimilated and dominated by this invading force. Their cinema was suppressed and largely used for propaganda purposes, if allowed at all, which forced more free thinking films to go underground during this period. After the war, there was a period of time that has been referred to as the Golden Age of Czechoslovakian Films that lasted throughout the 1960’s, but this too was curtailed by the invasion of the Soviets in 1968, forcing them into a communistic society. This oppression strained and narrowed artistic output for filmmakers, but several still attempted to express their thoughts and opinions through subtler means, such as using absurdist, metaphoric and darkly humorous stories. In this regard, one cannot separate the climate of the country from its film output.

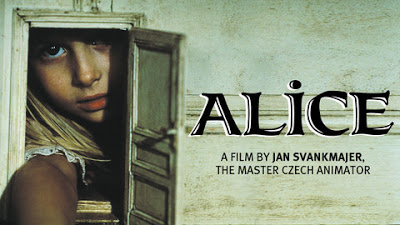

Jan Svankmajer was one such filmmaker during this communist period, who had previously been banned for the better part of a decade due to controversial filmmaking exploring the truth behind Czech life. His most famous work is Alice (1988, Svankmajer), a film that exemplifies that notion. The film acted as a subtle form of protest against the oppressive society in which it was made.

Within the film, Alice follows the White Rabbit, who is dressed as a nobleman and works closely with the King and Queen of Hearts. The character of Alice, representative of the Czech people, is constantly chasing after the rabbit, chasing after his status, but is constantly blocked by literal locked doors that she must figure out how to pass. Due to the enforced ideologies of the communist Soviets, social mobility was all but impossible, with the only way to move up from your position was often through underhanded and atypical methods, meanwhile those in the upper class had the doors opened for them, visually expressed as the rabbit having a literal key to move from room to room.

The film also expresses a dour view of this said ruling class. Later, during the trial, Alice is given a script to read from, confessing to crimes she hasn’t committed. This is not only reminiscent of forced confessions that were commonplace during this time, but also of the censorship of the filmmakers, and Jan Svankmajer himself. They were told what to say and in what way to appease the ruling class, and any sense of autonomy was dismissed. This is further represented that the court are all puppets and cutouts, none of them having true human qualities, but only facsimiles of them, and acting as puppets for the larger controlling entity that was the communist ideology. Svankmajer even has the Queen of Hearts continually skipping to the end, creating a sense of dark inevitability that the individual is doomed regardless of if they abide by or ignore the rules.

In the end, both Alice and Czech New Wave are a dark and surreal response to the socio-political climate their country were in at the time of their creation, an attempt to rage against the seemingly all-encompassing power that were their oppressors, and a reflection of the cultural consciousness being expressed in the most extreme and shocking ways.

Works Cited:

Karel, Srp (May 1999). Karel Teige in the Twenties: The Moment of Sweet Ejaculation